Difference between revisions of "The WUSTL Wireless Sensor Network Testbed"

(→Status) |

(→Status) |

||

| Line 82: | Line 82: | ||

==Status== | ==Status== | ||

| − | |||

==Acknowledgments== | ==Acknowledgments== | ||

Revision as of 20:39, 29 March 2018

|

| Contact: Dolvara Gunatilaka |

To facilitate advanced research in wireless sensor network technology, we are currently in the process of deploying a wireless sensor network testbed at Washington University in St. Louis. The testbed currently consists of 70 wireless sensor nodes (motes) placed throughout several office areas in Jolley Hall -- i.e., several grad student offices, the graduate student lounge, several labs, and conference rooms.

This document serves as an overview of the testbed setup and its current deployment. It is a living document in the sense that it will be updated as changes to the testbed continue to be made. In the end it will serve as a source of reference for anyone using the testbed to run sensornet related experiments.

Having a testbed of this size is important for a number of reasons:

- Only a handful of testbeds of this size exist in the world today. By being one of the first to have such a testbed, we will be able to conduct experiments that others have previously been unable to run. Our eventual goal is to make the testbed accessible through a simple web interface, opening it to users across the globe.

- Running large scale wireless sensor network experiments is hard. Programming a single mote can take up to five minutes depending on the size of the binary it is being programmed with. Without a testbed to streamline the process of programming a large number of motes, programming each mote individually can quickly become a significant bottleneck. Furthermore, as programming typically takes place by physically attaching a mote to your local machine, deploying them afterwards also takes a significant amount of time.

IMPORTANT:

Please keep in mind that the motes deployed in the testbed only contain sensors for light, radiation, temperature, and humidity. There are no microphones or cameras, and there is no plan to EVER include such sensors in the future. The purpose of the testbed is primarily for measuring communication characteristics of the motes and not evaluating the sensitivity or accuracy of its sensors. If you have any privacy concerns about including the testbed in your office please direct any questions to wsn@cse.wustl.edu.

Testbed Setup

Our testbed deployment is based on the TWIST architecture originally developed by the telecommunications group (TKN) at the Technical University of Berlin. The acronmym TWIST stands for "TKN Wireless Indoor Sensor network Testbed". It is hierarchical in nature, consisting of three different levels of deployment: sensor nodes, microservers (i.e., Raspberry PIs), and a desktop class host/server machine. A high level view of this three tiered architecture can be seen in the figure below.

At the lowest tier, sensor nodes are placed throughout the physical environment in order to take sensor readings and/or perform actuation. They are connected to microservers at the second tier through USB cables. Messages can be exchanged between sensor nodes and microservers over this interface in both directions. At the third and final tier exists a switch and a dedicated server which connects to all of the microservers over an Ethernet backbone. The server machine is used to host, among other things, a database containing information about the different sensor nodes and the microservers they are connected to. This database minimally contains information about the connections that have been established between the sensor nodes and microservers, as well as their current locations. The server machine is also used to provide a workable interface between the testbed and any end-users. Users may log onto the server to gain access to the information contained in the testbed database, as well as exchange messages with nodes contained in the testbed. The entire TWIST architecture is based on cheap, off-the-shelf hardware and uses open-source software at every tier of its deployment.

Having such an architecture enables one to perform tasks not feasible in other WSN deployments. For example, debug messages from individual sensor nodes can be sent to the control station over the USB interface without interfering with a WSN application running in the network. The USB infrastructure essentially provides an out of band means for collecting important information from each node without clogging up the wireless channel and adversely affecting any experiments being run. This debug information can also be time stamped by the micorservers using NTP (Network Time Protocol) in order to gather statistics about what is going on at each individual point in the network at any given time.

Programming of sensor nodes in the testbed is also made easier using the three tiered architecture, as a user simply tells the control station which sensor nodes it would like to program, and the control station does the work of distributing this request to the proper microserver. Information about which sensor node is attached to which microserver can be obtained from the testbed database, and each request can be sent to the proper microserver using a dedicated thread of control. These requests can then be processed by each microserver in parallel, speeding up the time required to program the entire testbed significantly.

Individual sensor nodes in the testbed can also be disabled or enabled the USB interface. This capability allows node failures to be simulated in the testbed environment, as well as fine tune the density of the network itself when running certain types of experiments. The introduction of new nodes into the network can also be simulated by enabling nodes at specific times during the run of an experiment.

All of the features described above really boil down to just one thing. It is possible to run sophisticated experiments in the WSN testbed without ever having to physically change the layout of the testbed or interact with the individual sensor nodes that make it up. Everything is controllable from the central server, and scripts can be written to perform countless numbers of operations involving each of the capabilites described above.

Existing Deployment

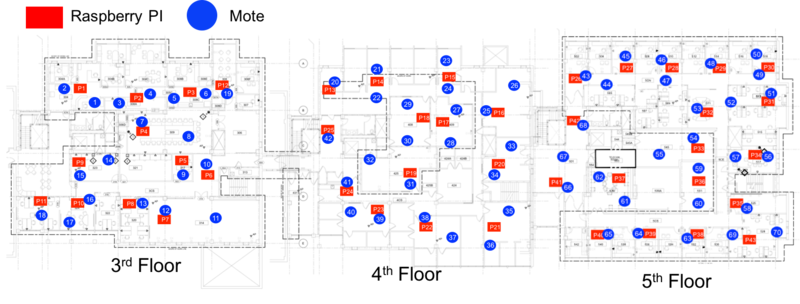

Currently the testbed consists of 70 TelosB motes placed throughout 3 floors of Jolley hall. The figure below shows the placement of these motes in the testbed. One to two motes are connected to each microserver, typically with one microserver per room.

Testbed Software

The testbed software has a client/server architecture, plus a set of user applications that interact with the wireless testbed. The client runs on the microservers and manages finding, programming, and communicating with the attached motes. The server coordinates the clients and the user applications. The user applications help the user to program, list, and communicate with motes in the system.

The client, server, and user application software has been written mostly in Python, with some performance-critical sections written in C. In addition, the server application interacts with a PostgreSQL database which lists the active microservers and motes. The PostgreSQL backend is also available for user applications to store experimental data.

Startup

The server software is automatically started as a Linux service on the testbed server machine. The client software is also installed as a service on the microservers but is not automatically started. A script is provided to the user which connects to the server and requests that the client be started on one or more microservers.

When the client service is brought up, it sends a status message to the server, which marks the microserver as "up" in the database. The microserver will also send messages listing the motes attached to its USB ports, which are likewise stored in the database.

Programming

To program a set of motes, the user runs the "program.py" script, passing it the program binary and a description of the motes to program. The user can select to program specific motes, all the motes attached to specific microservers, or the entire testbed. The server converts this request into a list of targeted motes.

Once the set of motes has been determined, the server creates a binary file for each mote. The server copies the original binary, imprints it with the mote's network address (stored in the database), and moves the new binary to the home directory of the microserver the mote is attached to. The server then passes a request to the microserver to flash the binary onto the mote.

When the programming completes, the microserver informs the server whether it was successful or not. The server collects this status for every mote in the programming set, and informs the "program.py" script when the job is complete.

The slowest part of programming a mote is flashing the binary onto the mote. Because the flashing takes place on the microserver, we can program motes on different microservers in parallel, allowing us to program the entire testbed in the time it takes to program the motes on a single microserver.

Serial Communication

The testbed software allows the user to send and receive serial packets through the motes' USB ports. When a microserver discovers a new mote attached to one of its USB ports, it opens a connection to the mote's serial port. Whenever a new serial packet is ready, the microserver reads the packet and sends it to the testbed server over the Ethernet backbone. The testbed server forwards each packet to end-user applications which subscribe to this data. Conversely, users may send the server requests to write a serial packet to a specific mote, which the server will forward to the corresponding microserver.

The TinyOS SDK normally provides a "Serial Forwarder" component that allows PC applications to collect data from a locally-attached mote. To interact with the testbed instead, the user runs the provided "forwarder.py" script, which acts as a drop-in replacement for the Serial Forwarder. Thus, existing applications developed using the standard TinyOS SDK can be used on the testbed without modifications.

Users may optionally use a testbed-specific Python API in place of the "forwarder.py" script. This Python API offers new features which are not provided by the standard TinyOS SDK, such as the ability to remotely reboot motes.

Status

Acknowledgments

This work is supported by the NSF under a CRI grant (CNS-0708460) and an ITR grant (CCR-0325529).